Iterative Nullspace Projection (INLP)

Shauli Ravfogel and Yanai Elazar

Welcome! this blog post describes our ACL paper on controlled removal of information from representations:

Shauli Ravfogel, Yanai Elazar, Hila Gonen, Micheal Twiton and Yoav Goldberg. Null It Out: Guarding Protected Attributes by Iterative Nullspace Projection. ACL2020

Calling neural models to order

Neural models are notoriously opaque. In recent years we witnessed an array of increasingly powerful models – from word representations to contextualized transformers – that capture many aspects of human language, ranging from the structural aspects of syntax, to more high level semantic aspects. But what can we do if we want to make sure that something is not encoded in the representation? This requirement arises in multiple scenarios. For example, we may want to have word embeddings that focus on lexical semantics, but discard the syntactic distinctions that are often encoded in the embeddings (e.g. tense); and to ensure fairness, we may want to have models that do not encode gender-related information, and do no rely on it.

It is tempting to assume that this problem can be solved by a preprocessing step, which eliminates from the training data the distinctions we do not want to encode: in our embedding-tense example, this can be lemmatization. While this solution is applicable in simple cases such as removing tense distinctions, it becomes much less practical when working with pretrained contextualized models, such as BERT, and when trying to eliminate more vague information such as gender distinctions. First, re-training large language models on new datasets is often impractical for standard practitioners. More importantly, it is not clear how to pre-process the training data, in order to remove gender distinctions: we first have to understand which parts of the input are causally responsible for the gender components in the encoding, and how to neutralize them. As we are about to see, societal concepts such as gender and race are deeply rooted in representations trained on neutral-language corpora, and are often represented in implicit and opaque ways. Naively removing gendered pronouns and first names from the training corpus does reduce the problem, but this is far from a complete solution.

What is currently known

Biases do exist

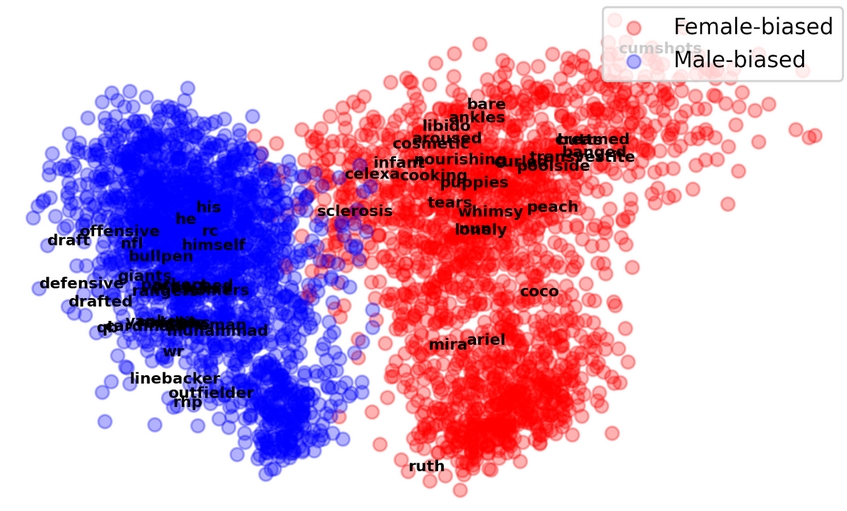

In recent years, a large body of work has shown that neural models capture subtle cues for protected attributes, such as the gender or the race of the person that wrote the text, of the text’s focus. The first works have focused on word embeddings, and they have shown that word embeddings capture and amplify many statistical differences between groups, that are reflected in the training corpora. For example, due to the imbalance between men and women in STEM fields, the representation of STEM fields such as mathematics is closer to male names than to female names. While this reflects an existing statistical tendency, the models can further amplify this trend; moreover, they can encourage the persistence of this imbalance, by causally influencing real-word decisions., for example, a CV-filtering system that is based on word embeddings, might consider the application of a female nuclear physicist an unlikely event.

Removing few predefined directions is not enough

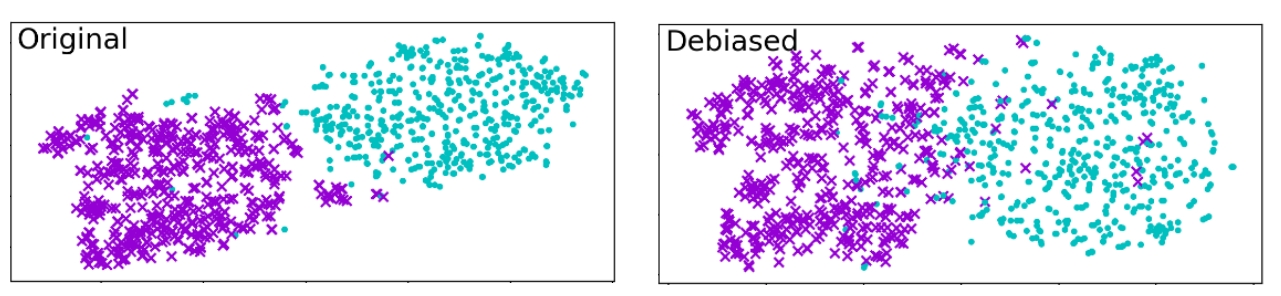

For word embeddings, one primary post-hoc “debiasing” method is the projection-based method of Bolukbasi et al. (2019). They aim to identify a gender direction in the embedding space, and neutralize it. Consider the direction defined as the difference between two inherently-gendered pairs, such as →he−→she. Subtraction of the two parallel but opposite words should leave us with a direction that supposedly captures (one) aspect of gender in the embedding space. We can delete the projection of each word embedding on this direction, and neutralize that aspect of gender. If one defines the gender content of an embedding as this projection, then we are done. However, Gonen and Goldberg (2019) have shown that this is not sufficient: even after we neutralize this direction, word vectors are still clustered very well by gender (see below, right plot).

Concepts are manifested in many ways

As we are going to see, gender is encoded in multiple directions, not all of them as interpretable as the →he−→she direction. the projection-based appraoch implictly assumes that gender is encoded in a very low-dimensional linear subsapce (e.g., the first principle coponent of few human-defined directions). In fact, gender is correlated with multiple orthogonal directions in the embedding space, which cannot be captured in a single direction. For instance, when we remove (using a technique we describe later) the information associated with the directions →he−→she, →John−→Mary and →father−→mother, we retain classification accuracy of 98.7%. When removing the first learned (rather than pre-specified) direction using our method we fare much better - gender classification accuracy drops to 86% - but is still significantly above random. Only after identifying and neutralizing 35 orthogonal directions do we get to random classification accuracy. While we demonstrated this on gender, we observed a similar phenomenon in many other concepts as well.

Adversarial removal is not exhaustive

When focusing on deep models, on the other hand, projection based methods are much less popular than adversarial training, where we regularize the training with an adversary which tries to predict the protected attributes from the hidden representations of the main-task models. Adversarial method show impressive performance in many tasks, such in domain adaptation for reducing the variability between domains. A similar approach was used to neutralize demographic features in the representations (e.g. 1, 2, 3).

However, Elazar and Goldberg (2018) have shown that even though using adversarial training can hinder the ability to identify some protected attributes in the representations, this method does not completely remove all the information, and it is often still can be recovered using a post-hoc classifier. Our method, which we describe below, can be seen as a special case of adversarial removal, where the adversary is restricted to be linear, and the dual-objective training (which is often unstable) is replaced with a deterministic projection layer. The restriction we impose on the adversary allows us to perform a deterministic removal operation, which we can interpret and even accompany with some guarantees, which we elaborate on in the paper. The resulting representation can then be used in applications, but, if the users want to take advantage of the guarantees, they should make sure to restrict themselves to a linear classification layer on top of it.

To wrap up, existing approaches mostly use either use projection-based debiasing, which is simple and elegant - but limited in power as it is based on neutralizing few human-defined “gender direction” – or adversarial methods, which are data driven and nonlinear, but are opaque and were shown to be not exhaustive. How can we enjoy the benefits of both worlds?

Enter Iterative Nullspace projections

We propose a method that generalizes the previous projection-based methods, and exposes their true potential. Unlike previous methods, we do not presuppose a few “gender directions”, but rather learn them from the data; and we perform an iterative process which aims to remove all gender directions. We begin with an intuitive description of our approach. Consider a linear probe model that is trained to predict gender from a representation. The model is parameterized by a matrix (or, in the binary case, a vector) W that can be interpreted as conveying information on directions in the latent space which are predictive of gender. If we could neutralize those directions, we could eliminate the main features in the representation which encode gender.

Luckily, when using linear probes, linear algebra is equipped with a simple operation that does just that: projection to the nullspace of W. Recall that the nullspace of W Is defined as N(W)= {x|Wx=0}, i.e. all vectors in the nullspace are mapped by W to the zero vector, and are orthogonal to W. They thus convey no information that is relevant to gender classification (according to that classifier). If we took the representation x and orthogonally projected it onto N(W), we’d end up with the closest point to the original x that is within the nullspace, and we’d neutralize the gender features used by W. The animation below gives a geometric demonstration of this idea in the 2-dimensional case:

Empirically we find that the latent space is approximately linearly separable by gender according to multiple different orthogonal planes. So we just repeat the process: we learn the first gender probe W1, calculate its nullspace N(W1) and the projection PN(W1) onto the nullspace, project the data to get a first “debiased” version PN(W1)X; and then we train the second gender classifier W2 on the “debiased” data, calculate its nullspace N(W2) and projection PN(W2), apply it to get a second “debiased” version of the data PN(W2)PN(W1)X, and so forth. We continue this process until no linear probe achieve above random accuracy. At this point we return the final “debiasing” projection P=PN(Wn)…PN(W2)PN(W1). This is the essence of our algorithm, which we call Iterative Nullsapce Projection (INLP).

Handling deep models

But what about deeper models? we take use of the fact they can be decomposed into a deep encoder and a final linear layer. We apply INLP on the final hidden representation, and potentially perform finetuning of the last linear layer afterwards. Since it’s linear, and INLP projection is not invertible, the linear layer cannot recover the removed information.

We test our method on increasingly complex settings: debiasing static word embeddings, deep binary classification and deep multiclass classification.

“Debiasing” word embeddings

We begin with removing gender associations from GloVe word embeddings. Following previous works, we annotate word vectors by gender bias according to their projection on the →he−→she direction. Initially, word vectors are clustered by gender bias:

The following animation displays t-SNE projections of the data points as the INLP process progresses It is evident that the vectors become increasingly mixed, and are no longer clustered by gender. We also quantified this effect using a measure for cluster purity.

We used WEAT to measure whether the transformed vectors still show undesired associations between socially-biased terms and female and male names. Those associations are strong from the original embeddings, but became insignificant following INLP.

Debiasing: in the wild

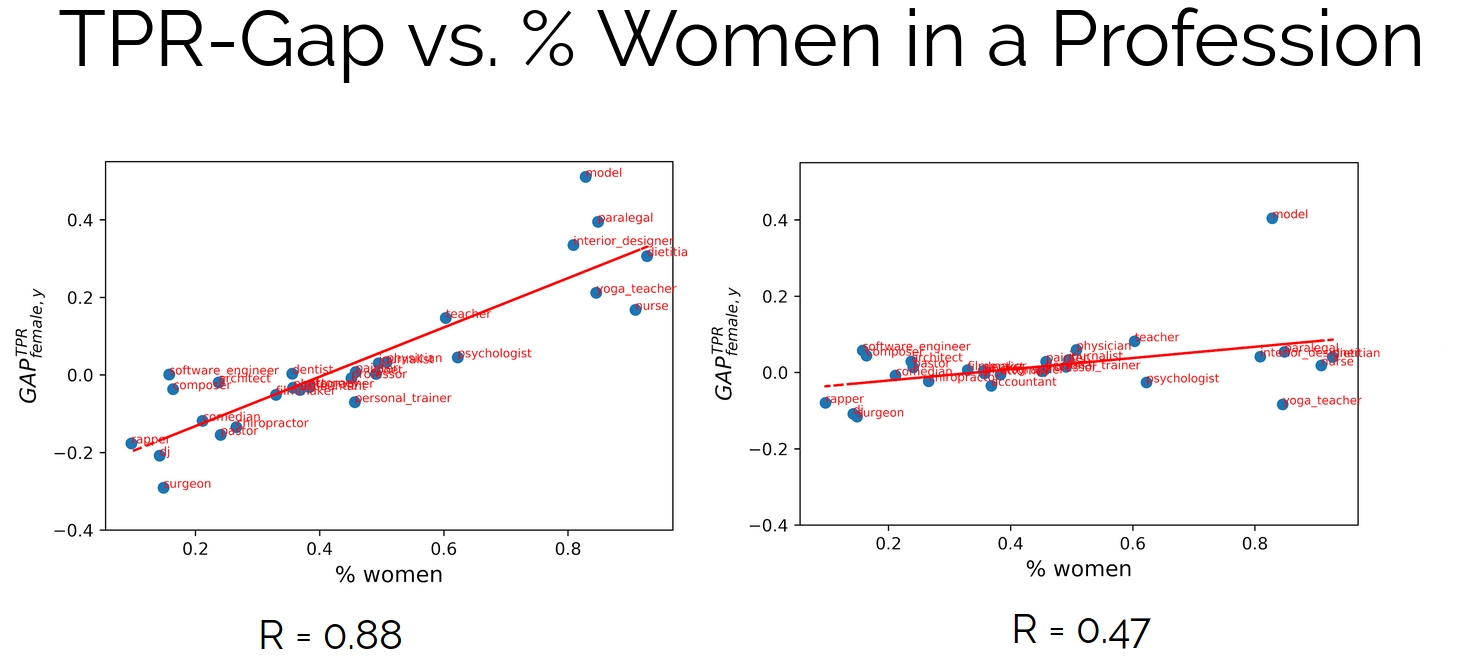

Finally, we test our method on a multi-class fair classification setting. We use the profession-prediction datasets presented in De-Arteaga et al. (2019). The dataset contains short biographies, divided into 28 professions and annotated by gender. It has been shown that models trained on this dataset tend to condition on gender, due to the imalanaced representation of men and women in some professions. We use 3 models: bag of words, bag of word vectors, and BERT. In all cases, we perform INLP on the last hidden representation, and then finetuned the last linear layer. The intervention decreases the True Positive Rate Gap (TPR-Gap) between men and women, and the correlation between the bias and the percentage of women in each profession is mitigated:

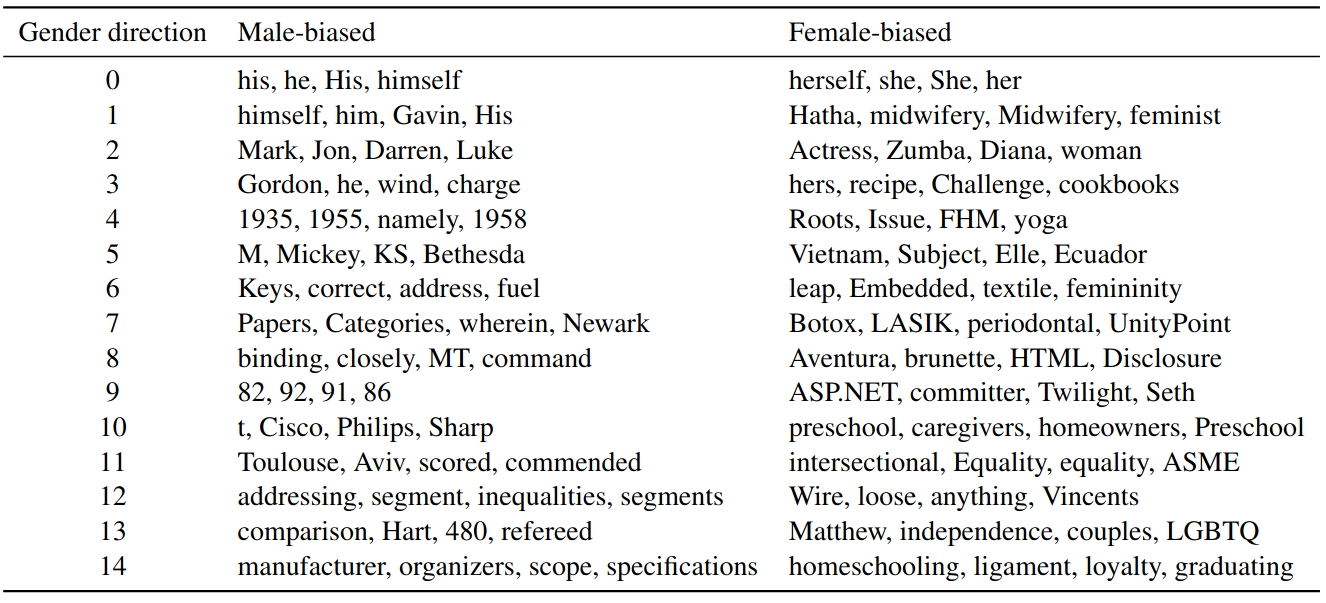

We noted earlier that in INLP we treat the classifiers we train for the prediction of the protected attributes, as conveying information on latent features that are correlative to the property we focus on. We can emrbace this view to shed light on the different facets by which gender bias is manifested in neural models. We used the bag-of-word-embeddins model for the biographies dataset, and inspect the top 15 gender directions identified by INLP. we then inspect the closest words to each of those directions:

Interestingly, many of of the directions are interpretble: the first direction seems to capture gendered pronouns; the third ones – first names ,and other gendered words; and more. At the same times, some gender associations are harder to interpret, for instance the association between “manufacturer”, “specifications” and “addressing” with male biographies. It is not clear if those represent merely spurious correlations, or whether they reflect actual subtle differences between the biographies of men and women.

What’s next?

We have identified two key weaknesses of previous projection-based information-removal methods, and proposed a new method which is both data-driven and exhaustive. We see this method as a strong alternative to adversarial removal of information: while we focused on gender as a case study, one can use INLP to selectively remove any kind of information from representations, in a controlled manner - provided that we have annotation for that property. This can also serve as a behavioral test: we can remove some information, and inspect how does its removal influences the behavior of the model in some other main task (e.g. language modeling).

Moreover, one can use INLP to study the information we focus on, rather than to neutralize it. Recall that in INLP we identify a set of directions in the latent space which correspond to the protected attribute. While in the conventional use we discard those directions, in a complementary setting we can alternatively discard all other directions, maintaining only the components of the representation space that are related to it. Under this setting, INLP serves as a supervised dimensionality reduction method: we distill the part of the representation we are interested in. This can have multiple use cases: exploring BERT’s “syntactic subspace” (e.g. by using INLP to find the subspace that encodes dependency edge identity); analyzing BERT “gender subspace” (which sentences are close in that subspace, but not necessarily in the original representation space? which phrases influence the representation on the gender subspace – and which do not?); and more. we hope that this work would shed more light on the intricate and subtle ways bias is represented. More generally, we see it as another step forward towards the goal of achieving controllable representations, which can safely find real-world applications.

A word of warning

Since bias can have real world ramifications, one should always be cautious when examining claims on bias mitigation. Naturally, as a research paper, we worked on certain datasets and examined only several notions of bias. It is certain that INLP does not neutralize all gender content from the representations. In addition, it only aims to remove linearly-present information: while we show it can also be successfully applied to deep models, the user is responsible not to use nonlinear layers on top of it.

Try it out!

We release the code and models used in this work, to foster new applications and usages, as well as reproducibility.